Gilda Radner So Funny I Forgot

T here is no shortage of excellent critical writing about the US comedy scene in the 80s, and Nick de Semlyen's Wild and Crazy Guys, which is published in the UK next month, is a terrific contribution to the genre. De Semlyen frames his book by telling the stories of the men who forged that world, most of whom – including Chevy Chase, John Belushi, Bill Murray, Eddie Murphy and Dan Aykroyd – emerged from the comedy training ground of Saturday Night Live. But what De Semlyen's book also shows is that this scene was dominated by men. Yet that wasn't supposed to be the case.

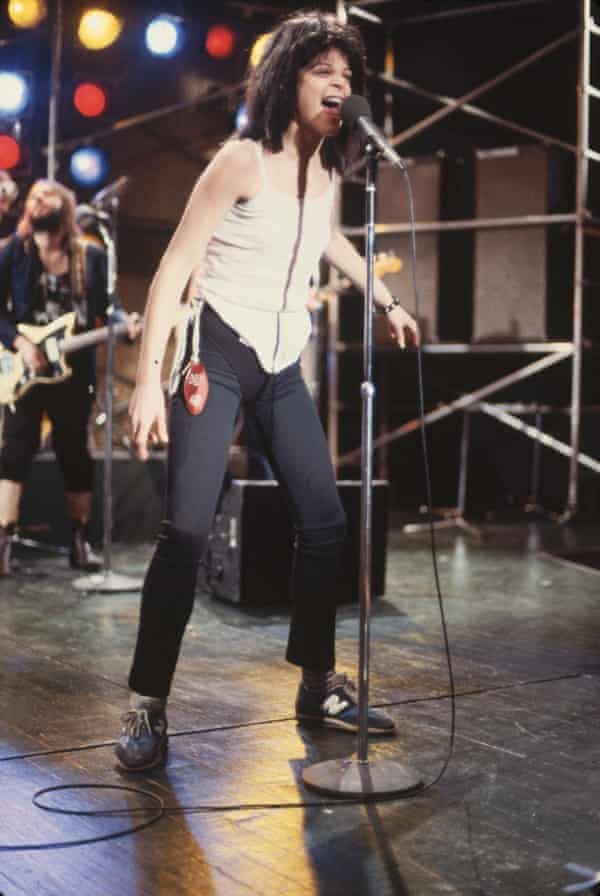

This month is the 30th anniversary of the death of Gilda Radner, one of the original cast members of SNL, alongside Chase, Belushi, Aykroyd and others. Although she is comparatively little known today outside comedy circles, back then she was widely assumed to be the future megastar of that group. With her sharp parodies of celebrities and her skill at satirising her own femininity and neuroses, she set the mould for modern female comedians. Without Radner, it is hard to imagine the existence of many of the most beloved comic characters of the past 30 years, from Elaine Benes in Seinfeld to Liz Lemon in 30 Rock.

The NBC president at the time, Fred Silverman, saw in her a Mary Tyler Moore for the 80s and desperately wanted to build a primetime variety show around her. When Radner decided she would rather stay with her original supporter, Lorne Michaels, the creator of SNL, the relationship between Silverman and Michaels was irreparably damaged. Michaels had so much faith in Radner's star power that in 1979 he produced a Broadway show just for her, Gilda Radner: Live from New York, in which she performed her best-known and much-loved characters from SNL, including Baba Wawa, her superlative parody of Barbara Walters; Roseanne Roseannadanna, an eccentrically offensive reporter; and Emily Litella, a doddery news commentator who never quite understood the story.

The show was a huge success. "She combines the physical humour of Lucille Ball with the diverse characters of Lily Tomlin," wrote the New York Times. If things had gone as they should have, Radner would be as famous today as both of them. Instead, as she wrote in her hilarious and devastating memoir, It's Always Something: "There was a time at the height of Saturday Night Live when I couldn't even walk down the street in New York because every single person recognised me. It got so that I didn't even go out because of that kind of attention. Now I'm someone people shout 'Hey, you, move!' at in the parking lot of a hospital."

Radner grew up in a Jewish family in Michigan. She was the first person Michaels cast on SNL in 1975. While the men, especially Belushi and Chase, grabbed the headlines for their bad behaviour off screen, Radner was the cast member most cherished by the public and her colleagues. She was as comfortable with broad pratfalls as with character-based comedy and she had a goofy warmth that charmed everyone. "She was the sweetest, kindest, funniest person. She had such a happy face on camera that you really did grow to love her," said Steve Martin, a frequent guest on the show. She was quickly named "America's sweetheart" by the press. "Gilda was really an extraordinary and spectacular person. I never enjoyed making anyone laugh more than her. Never," said Bill Murray, her friend (and ex-boyfriend), in Live from New York, Tom Shales and James Andrew Miller's history of SNL. Her talent and appeal were so great that even Belushi – who would refuse to perform a sketch if he knew a woman had written it – always treated her with love and respect. "He thought Gilda was funny, but ... he didn't classify her as a woman. She was Gilda," said their fellow SNL cast member Jane Curtin in a recent interview.

Whereas many of her fellow cast members self-destructed with drugs, Radner found other ways to do so. "I coped with stress by having every possible eating disorder from the time I was nine years old … I wasn't interested in drugs because I had food," she wrote in her memoir. Sometimes she would invite SNL cast member Laraine Newman over to her apartment; while Radner would binge and purge, Newman would snort heroin. "There we were, practising our illnesses together. She was still funny throughout it all," Newman recalled. Her SNL performances occasionally played on the fragility others sensed in her. In one skit – which, with horrible prescience, played on her lifelong terror of cancer – she sang a song called Goodbye Saccharin, about how she would rather eat carcinogenic sweeteners than sugar because her fear of getting fat was marginally greater.

But, as fragile as she may have seemed, it took steel to survive not only the notoriously punishing schedule of SNL, but also SNL in the 70s, when it was at its most sexist. "There were a few people who just out and out believed that women should not have been there and that women were not innately funny," Curtin recalled. Amy Poehler said it was thanks to these women, singling out Radner, that her generation of female SNL comedians could break in: "The sketch women who came before me – Andrea Martin, Catherine O'Hara, Gilda Radner – hung in there in a really misogynistic, aggressive, macho environment and they just weathered the storm like a news reporter reporting on a hurricane. And then our generation came in and we were better for it." Radner was so unfazed by SNL's notorious boys' club atmosphere that she didn't even mention it in her memoir.

With the selective editing of hindsight, it is often assumed that the early SNL alumni all tumbled out of the show and straight into hit movies. But the truth is more complicated. Chase, Aykroyd and Belushi flailed around for years in bad comedies and worse dramas before Chase finally hit it big with the National Lampoon movies and Aykroyd struck gold with Trading Places. (Tragically, Belushi died before he found his post-SNL movie feet beyond The Blues Brothers.) Even Eddie Murphy – unquestionably the most successful SNL cast member – chose an absolute turkey, Best Defense, for his first movie after leaving the show. Radner left SNL in 1980 and largely her films have not endured, but it is impossible to say what she would have done had she not fallen ill a handful of years after leaving the show.

In any case, she had another count against her. When it came to sketch comedy in the 70s and 80s, "the ratio was five to one in terms of men and women", says the director and producer Ivan Reitman in Wild and Crazy Guys. "In general, there was a reluctance to do movies that starred women, in all of Hollywood. It was partially about what would work in the international market. And the comedies that ended up working were more action-based or physical ones, which were more male-oriented."

But Radner did have one piece of luck in her film career: while making the 1982 comedy Hanky Panky, she met Gene Wilder. "Gene was funny and athletic and handsome and he smelled good. I was bitten with love and you can tell it in the movie. It wasn't good for my movie career, but it changed my life," is how she opened her memoir. Radner's descriptions of her almost frantic love for the twice-divorced and now marriage-resistant Wilder are the most purely funny sections of her book and feel like precursors of Bridget Jones: "I had plenty of time to get dinner on the table and involve Gene in endless conversations about commitment and meaningful relationships and child-rearing and meaningful relationships and commitment." Perhaps more revealingly, she adds: "My new 'career' became getting him to marry me. I turned down job offers so I could keep myself geographically available." Radner's efforts paid off and she and Wilder got married in 1984. But they barely had any time to enjoy their marriage.

Radner desperately wanted to have a baby with Wilder – "Imagine the hair!" – but she repeatedly had miscarriages. She thought this was due to an illegal abortion she had in the 60s, but pain in her abdomen suggested there was another problem. Doctors dismissed her complaints until, after months of sickness, she was diagnosed with stage four ovarian cancer. She was 40. She immediately underwent a total hysterectomy, ending her dreams of having a child, but guaranteeing her survival.

Or so she thought. For the next few years, her life was a horrific rollercoaster of chemotherapy and radiation, promises of being free of cancer, only for the cancer to recur. Meanwhile, her contemporaries were enjoying enormous professional success. "Unlike most people, I see people I know on TV, my whole peer group, people I grew up with," she wrote. "I imagined being interviewed on television: 'Gilda, what are you doing now?' 'I'm very busy. I'm battling cancer.'"

What made this twist of fortune even more cruel was that it came just as her life was turning around: "In the three years before my cancer diagnosis, I had begun to change. Through therapy, and with Gene's help, I had overcome my eating disorders. I suppose what was happening was that I was beginning to care about my life."

Few of her former comedy colleagues understood how ill she was because she didn't want them to. She withdrew from most of them and those who came to visit her at home were impressed at how the house seemed to be filled with friends. It wasn't until later that they realised these "friends" were nurses whom Radner had instructed to pretend they were paying a social visit.

On the last page of her memoir, Radner wrote: "I wanted to be able to write on the book jacket: 'Her triumph over cancer.' I wanted a perfect ending. Now I've learned the hard way that some poems don't rhyme and some stories don't have a clear beginning, middle and end. Like my life, this book has ambiguity." Not long after writing that, Radner was told her cancer had returned, again. During a CT scan, she fell into a coma. She died three days later on 20 May 1989, with Wilder holding her hand.

The cast and crew of SNL were told of her death just before the show was due to air. By chance, Martin was hosting that night and he junked his planned opening monologue. Instead, with a strained face, he talked with an audible lump in his throat about how the greatness of the show lay in "the people you get to work with". He then showed a clip from 11 years previously: a dance routine he and Radner had done, a pastiche of a scene from the Fred Astaire-Cyd Charisse musical The Bandwagon. Radner looks so vital, so beautiful; even though the joke is that she is a klutz, there is a heartbreaking grace to her. As a comedian, Martin has often been accused of being cold, or at least emotionally detached, but when the clip ended and the camera cut back to him, his face was crumpled in a suppressed sob. "Gilda, we miss you," he managed to say before his throat closed up.

In the years immediately after her death, Radner's most obvious legacy was a massive increase in awareness of ovarian cancer and how certain factors – such as a family history of cancer, which she had – contribute to the risk. Wilder devoted himself to this cause, establishing the Gilda Radner Hereditary Cancer Program to screen those deemed high-risk. He also testified before a congressional committee about how Radner's doctors repeatedly missed warning signs.

But her comedic influence, too, has become increasingly obvious as time has gone by, as those who grew up watching her have become comedians in their own right. This is especially true of female comedians. Lena Dunham has talked about collecting Radner memorabilia – posters, photos, Roseanne Roseannadanna playing cards – and Maya Rudolph has recalled staying up late as a child to watch Radner on SNL. Last year, the documentary Love, Gilda screened in the US. In it, Melissa McCarthy, Poehler, Rudolph and more talk about the huge impact Radner had on them. But perhaps the most obvious inheritor of Radner's crown is Tina Fey, who, on SNL, became similarly known for her personal satires and, through Liz Lemon on 30 Rock, riffed on the anxieties that come from being a working woman in a big city, just as Radner did. "She was our equivalent to Michelle Obama. She was so lovely and she was so authentically herself and so regular in so many ways … We all saw that and said: 'I wanna do that,'" Fey said last year when introducing the premiere of the film.

In her memoir, Radner marvelled at how her name was once associated only with comedy, but "has now become synonymous with cancer. What good is that going to do?" Her death at 42 was a cruel personal tragedy, but Wilder, in the depths of bereavement, strived to give it meaning and used it to help prevent other women enduring what Radner had gone through. Now, things have gone full circle: thanks to the current generation of high-flying female comedians, she is synonymous with comedy again. "I thought I could control my chances of getting cancer by being neurotic and funny about it. But it doesn't work," Radner wrote. It doesn't. But, by being funny about even the worst of life, Radner ensured that her influence will never die.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2019/may/07/she-was-our-michelle-obama-how-gilda-radner-changed-comedy-for-ever

0 Response to "Gilda Radner So Funny I Forgot"

Post a Comment